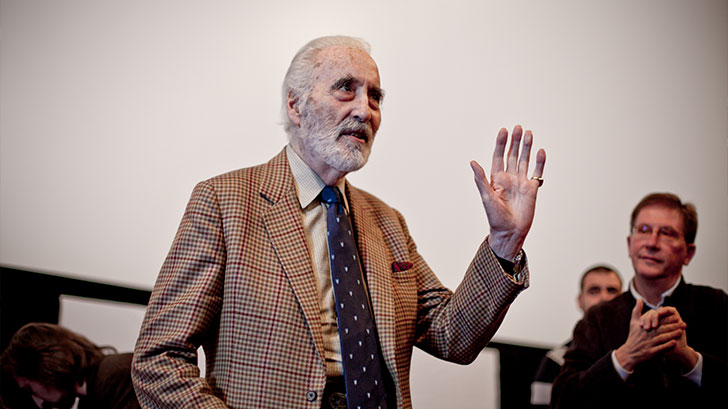

Christopher Lee

Premio Urania d’argento alla carriera 2009

Born in London in 1922, Christopher Frank Carandini Lee, son of an Italian Countess and a British army officer, made his acting debut in the title role of Rumpelstiltskin during an unhappy spell at a Swiss school.

‘I learnt at the outset that the best lines are given to the baddies and that these make the most impact on the audience.’ After war service as an Intelligence Officer, Lee drifted into acting, with a spell in producer J. Arthur Rank’s infamous Charm School.

Though considered ‘too tall and foreignlooking’ to be a star, Lee became a busy jobbing character man from his first days in the business – his first screen work came in 1947 with a primitive live TV show Kaleidoscope and the film thriller Corridor of Mirrors.

In the next ten years, Lee’s film work ranged from unbilled bits (shouting ‘lights’ in Olivier’s Hamlet, his first film with Peter Cushing, Seurat in John Huston’s Moulin Rouge) to leads in B pictures (a split personality killer in Alias John Preston), and a great deal of TV repertory work (Douglas Fairbanks Presents, Errol Flynn Theatre).

His height and ‘foreign’ looks, plus a facility for languages and dialects, won him roles like the Spanish Captain in Captain Horatio Hornblower RN, a Swedish policeman in Valley of Eagles, a Uruguayan barman in The Battle of the River Plate, a Nazi officer in Ill Met By Moonlight and the sadistic Marquis St Evremonde in the Dirk Bogarde version of A Tale of Two Cities. That he didn’t fit into the literal ranks of British 1950s cinema, with its division between ‘officers’ and ‘men’, was demonstrated by his odd turn as a cockney NCO in Nicholas Ray’s Bitter Victory. Nevertheless, the eagle-eyed afternoon television addict can spot Lee in the likes of Scott of the Antarctic, Trottie True, They Were Not Divided, Prelude to Fame, The Crimson Pirate, Innocents in Paris, Storm Over the Nile, The Cockleshell Heroes, Private’s Progress and Fortune is a Woman.

The turning point in Lee’s career came in 1957 when Hammer Films, having had a hit with the black and white science fiction monster movie The Quatermass Experiment, decided to put the boat out on a colour remake of the classic monster movie, with Terence Fisher directing and Jimmy Sangster scripting The Curse of Frankenstein. In this version, the star role was Baron Frankenstein, played by the equally busy but then far-better-known Peter Cushing, but Hammer needed someone tall to play the Monster. Bernard Bresslaw’s agent asked for too much money so Christopher Lee went down to Bray Studios and was plastered with gruesome make-up. The film was a hit, but Lee didn’t get the recognition he deserved: acting in the flat-headed shadow of Boris Karloff, whose reading of the role was definitive, Lee’s Creature doesn’t stir to life until an hour into the film and is mostly an animal-like threat, disposed of by a dunk in an acid bath that meant sequels could bring back the Baron but would need new monsters. However, it’s a frightening and affecting cameo, with one great moment as the already-hideous Creature is displayed after a brain operation with fresh scars among the old ones and turns away with a pathetic vanity, trying to conceal his one new deformity. ‘My face was hidden by scarring tissue, my body by bandagewrapping; I was nothing but a mobile parcel,’ said Lee. ‘But then Dracula came along and I knew this was going to be a long-term career if I wanted to follow in its path.’

The Curse of Frankenstein was such a hit that Hammer took no risks in planning follow-ups, retaining stars, director, writer and many other cast and crew members for the inevitable Dracula (aka Horror of Dracula). Though again on screen for a very short time, Lee clearly walked away with the film, briskly suave when putting a guest at ease and then a hissing, fanged savage when pouncing. The cape flaring, boudoir-invading Count has a very phsyical final confrontation with Cushing’s Van Helsing, making this Dracula a supernatural swashbuckler, paying off with a fine disintegration-at-dawn scene. After that, Lee was a horror star to equal Cushing, but Hammer seemed not to notice. In The Mummy, he was under bandages again, impressive and impassive in a role more suited to a stuntman. Then, Hammer handed him stock supporting villain or hero in The Hound of the Baskervilles, The Man Who Could Cheat Death, The Two Faces of Dr Jekyll, Taste of Fear, The Gorgon and She. The company even made sequels to his star-making hits without him, bringing back Cushing for The Revenge of Frankenstein and The Brides of Dracula.

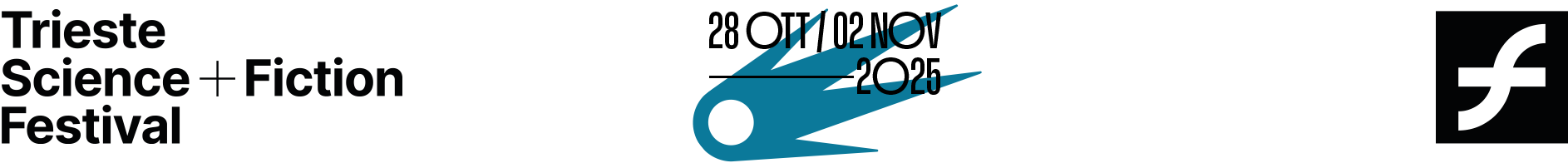

Meanwhile, other producers in the UK and across Europe offered meatier horror roles: a bodysnatcher opposite genre legend Boris Karloff in Corridors of Blood, a parody vampire in the Italian Tempi duri per i vampiri (aka Uncle Was a Vampire), a mephistophelean magician in the French The Hands of Orlac, a Satanist professor in City of the Dead (aka Horror Hotel).

He even turned up in a couple of thinmoustached Soho strip club spiv roles, Beat Girl and Too Hot to Handle. Hammer finally gave him lead roles, but in exotic adventure films (The Terror of the Tongs, The Pirates of Blood River, The Devil-Ship Pirates) while casting Herbert Lom as their Phantom of the Opera, Paul Massie as Jekyll and Hyde and Cushing as everyone else.

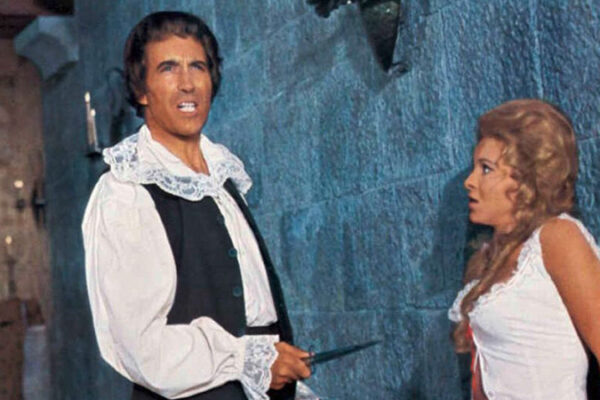

Throughout the 1960s, Lee hopped around Europe, still playing leads and character bits as required, making extraordinary, ordinary and atrocious films. For Italy’s Mario Bava, he made Ercole al centro della terra (aka Hercules in the Haunted World) and the remarkably sado-romantic La frusta e il corpo (aka The Whip and the Flesh), then popped back for sinister gothic roles in Camillo Mastrocinque’s La cripta e l’incubo (aka Crypt of Terror), Antonio Margheriti’s La vergine di Norimberga (aka The Virgin of Nuremberg) and Herbert Wise and Michael Reeves’s Il castello dei morti vivi (aka Castle of the Living Dead). In Germany, he contributed to the Edgar Wallace cycle (Das Rätsel der roten Orchidee aka The Secret of the Red Orchid), made another odd vampire movie (Das Schlangengrube und das Pendel aka Blood Demon) and played Sherlock Holmes (Sherlock Holmes und das Halsband des Todes aka Sherlock Holmes and the Deadly Necklace). Hammer’s rivals started employing him with far more imagination: hence varied credits in allstar horrors for Amicus (Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors, The Skull, The House That Dripped Blood), American International (The Oblong Box, Scream and Scream Again), Tigon (Curse of the Crimson Altar, The Creeping Flesh), even Planet (Night of the Big Heat) and Pennea (Theatre of Death). He commenced a new semi-horror cycle for producer Harry Allan Towers with The Face of Fu Manchu in 1964, returning (as promised in the ritual finale of the Devil Doctor’s booming voice laid over the image of his latest exploding lair) to the role of Sax Rohmer’s diabolical mastermind four times, though the series passed from the respectable Don Sharp (Brides of Fu Manchu) past Jeremy Summers (The Vengeance of Fu Manchu) to the indefatigable but only intermittently Jesus Franco (Castle of Fu Manchu, Blood of Fu Manchu).

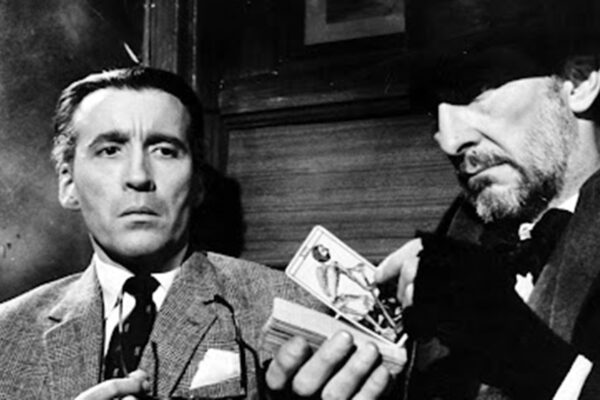

Hammer finally upgraded Lee to Most Valuable Player status in 1965 by signing him up for a reprise of his greatest role in Dracula, Prince of Darkness, made back to back with the historically marginal but otherwise interesting Rasputin, the Mad Monk, and then cast him in a dashing, heroic role in a project he had advocated at the studio, Dennis Wheatley’s The Devil Rides Out. Despite the success of the Wheatley film and growing evidence of Lee’s versatility, Hammer only called him back to the cape and fangs in films that hardly seemed worth the effort for the actor, whatever their other strengths and failings: Dracula Has Risen From the Grave, Taste the Blood of Dracula, Scars of Dracula, Dracula A.D. 1972 and The Satanic Rites of Dracula. Though he made a brave stab at a different reading of the role for Franco in El conde Drácula (aka Count Dracula), explored its context in the short In Search of Dracula, played Count cameos in One More Time and The Magic Christian and delivered more parody in Dracula, père et fils, Lee spent a great deal of time insisting in interviews and demonstrating on screen that his range extended beyond biting starlets and swishing his cloak. In the early 1970s, taking a more pro-active role in his career, Lee set up his own projects loosely within the horror genre (often teaming with Cushing) – playing Jekyll and Hyde in Amicus’s compromised I, Monster, producing and starring in the macabre thriller Nothing But the Night, and sparring with Cushing in the endearingly daft Pánico en el Transiberiano (aka Horror Express).

In this period, he lent his presence to Robin Hardy’s remarkable The Wicker Man and Hammer’s last horror gasp, another Wheatley tale, To the Devil a Daughter.

Low- and medium-budget horror made Lee a star, but he pushed the genre envelope with roles in major productions: as Sherlock Holmes’s cleverer brother Mycroft in Billy Wilder’s sorely underrated The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, as the eye-patched swordsman Rochefort in Richard Lester’s The Three Musketeers and its follow-ups and as a Bond villain in The Man With the Golden Gun. In the mid-70s, Lee relocated to Hollywood, and turned up in shaky all-star efforts like Airport ’77, Return From Witch Mountain, Caravans, Bear Island and Steven Spielberg’s 1941. He also did TV movie villains (Captain America II), hosted Saturday Night Live, guested on Charlie’s Angels, played an alien priest in End of the World, impersonated the Duke of Edinburgh in Charles and Diana: A Royal Love Story and somehow wound up in Hollywood Meatcleaver Massacre and Howling II: Stirba, Werewolf Bitch (while turning down the Donald Pleasence role in Halloween). In Britain, Pete Walker’s House of the Long Shadows was a disappointing last hurrah for horror stars – alongside Vincent Price, Peter Cushing and John Carradine – but Lee had more rewarding moments in the Australian superhero parody The Return of Captain Invincible and Joe Dante’s Gremlins 2: The New Batch.

Returning to England and European career opportunities, Lee became a miniseries king, often in period or exotic roles like older versions of the types he had played in the 1950s. After roles in The Far Pavilions and Shaka Zulu, he appeared in standout cameos in versions of Casanova, Around the World in 80 Days, The French Revolution, Moses, Treasure Island and The Odyssey, and revived an old role for Sherlock Holmes: The Golden Years.

Though he did the odd tiny horror film (Panga, Funny Man, Talos the Mummy) in the 1990s, his credits remained as eclectic as ever, with a segue from straight man in Police Academy: Mission to Moscow to above-the-title star in Jinnah, an epic which tried to do for Pakistan’s founder what Richard Attenborough had done for Gandhi. At an age when most actors would consider retirement and polish their Life Achievement Awards, Lee – perhaps to his surprise – found himself enjoying the most high-profile work of his career. The late 1990s brought a significant cameo in Tim Burton’s Sleepy Hollow, a major role in the TV dramatisation of Gormenghast and a star turn reading M.R. James in the BBC’s Ghost Stories for Christmas, while the turn of the century led an actor approaching 80 to parts in blockbuster franchises – the ‘charismatic seperatist’ Count Dooku in George Lucas’s Star Wars, Episode II: Attack of the Clones and the white-wizardgone-bad Saruman in Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy. He is also in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, The Golden Compass, The Colour of Magic (as the voice of DEATH) and Alice in Wonderland.

Knighted in 2009, even as a revived Hammer Films cast him in The Resident, Sir Christopher Lee continues to grace the cinema with his magisterial, yet versatile presence.